- Home

- Goran Vojnovic

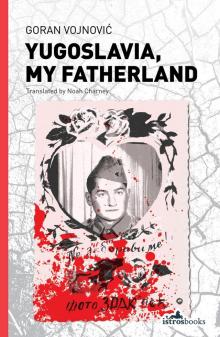

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland Read online

GORAN VOJNOVIĆ

YUGOSLAVIA, MY FATHERLAND

Translated from the Slovene by Noah Charney

To Barbara.

First published in 2015 by Istros Books

(in collaboration with Beletrina Academic Press)

London, United Kingdom

www.istrosbooks.com

Originally published in Slovene as Jugoslavija, moja dežela by Beletrina Academic Press

© Goran Vojnović, 2015

The right of Goran Vojnović to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Translation © Noah Charney, 2015

Cover design and typesetting: Davor Pukljak | www.frontispis.hr

Cover photograph courtesy of Naklada Postscriptum, Zagreb, Leksikon YU mitologije

ISBN: 978-1-908236-272 (printed edition)

ISBN: 978-1-908236-777 (Ebook)

This Book is part of the EU co-funded project “Stories that can Change the World” in partnership with Beletrina Academic Press | www.beletrina.si

The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

MAP OF SFR YUGOSLAVIA

1

It must have been a normal, early summer day in 1991, when my childhood suddenly ended. The day was heavy and close, and since early morning, the grown-ups had been saying it would rain that afternoon, while the children wondered why people who didn’t even have tomatoes or courgettes planted in their gardens, would summon rain in the middle of the prime swimming season. Our world at the time was a far cry from the one our parents seemed to inhabit. For most of us, grown-ups were creatures from a distant planet, only worth noticing if they were missing an arm or a leg, if they had a wild, long beard down to their toes, dressed like an Indian or had tattoos on their backs, or giant biceps like Rambo, with all his sequels.

On that sultry morning we set off to see one of those rare, interesting grown-ups. Mario and Sinisha couldn’t believe that I had yet to see the guy with the red lump on his face. It was just a big brain tumour; at least according to some, while others were convinced that it was something called bulimia, a new disease that had recently been discussed on TV, and which turned a person’s head into a huge red lump, or so Sinisha claimed. Mario claimed that everyone aside from me had already seen the guy with the lump, while Sinisha recounted one escapade after another featuring Lump Guy as protagonist. According to the biggest bigmouth in Pula, a German tourist took one look at Lump Guy and started to back away from him, and walked backwards the mile or so back to her hotel. An Italian family was even supposed to have notified the police and the Italian embassy in Belgrade about him. Mario and Sinisha both said that I just had to see Lump Guy, cause how often can you see someone with only half of his head normal, while the other half was inflated like a basketball and as red as a sliced watermelon? It didn’t take long to convince me and, in no time, we were marching together past the shop and towards the workers’ dormitory.

A humdrum, white rectangular building housed the guy with the lump, as well as the workers who, following their hard working days at the shipyard, would sit peacefully in front of the entrance, sipping their beers, and chewing over their Bosnian topics. Even though they lived just around the corner from our apartment buildings, they lived in their own parallel – and almost invisible – world. They fraternized only with each other, and gathered in the evenings in the common room on the first floor of the dormitory to watch the news, a live broadcast of a football match, or some series on national TV.

Along the way, my well informed friends explained that, during the day, Lump Guy vegged out in front of the box and watched TV Zagreb, motionlessly: everything from the domestic family sagas to documentaries picked by the head of Croatian national television. Sinisha told me rumour had it that Lump Guy’s room-mates had once collected money, bought him a small portable television set and installed it in his room, but he kept hanging out in the common room, though he never spoke to anyone. Mario added that Vaha, the welder, once tried switching the program every ten minutes, but Lump Guy hadn’t reacted at all, as if he didn’t give a damn what he was watching.

As I listened to these stories, I approached the entrance of the dormitory with high expectations, almost as high as when we set off to visit a circus tent next to the Istra Football Club stadium, on the eve of the circus’ premiere, to secretly observe performers practice. But before we had crawled through the tall grass and managed to peek inside, a small screaming Gypsy girl scared the shit out of us, and we ran like headless chickens from that tiny black creature.

That day at the workers’ dormitory turned out wholly different than expected. Instead of encountering a lone guy with a lump, the tiny TV room was packed, everyone staring at the television screen, on which the news was unwinding. The atmosphere was similar to the previous year, when a similar euphoria possessed the single men after Piksi’s second goal at that unforgettable quarterfinal match of Yugoslavia against Spain. That time, only the police could restore order, and Ramo ended up at the ER, because he had been got an electric shock while French kissing the television set and the antenna.

Twelve months later, Sinisha, Mario and I were looking for the ‘watermelon man’ in the multitude of supporters cheering on the noon TV news, and were surprised to find that only a small part of those gathered supported the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. One could see from afar that the group was led by Milo Lola Ribar, who could down a case of beer solo, and was shouting louder than anyone ’fuck Yugoslavia,’ for having bottomed out last year against those Serbo-phobes from Argentina, and that he was no longer interested in the sport. Next to him, and right next to the TV, stood Little Mirso, a sixteen year old with a face more adult than a soldier’s and behaviour to match, who warned all those present, in the most serious manner, that sunbathing, ferragosto and fireworks were over in the Arena, but he did not say why. Plenty of amateur screamers were gathered there in the hall of the dormitory, their plain, flat voices forming an incomprehensible wall, even though their flushed faces told us that they were doing their best.

Cera, a famous cinema operator from Pula, stood at the entrance, where it was so crowded that we got stuck, jammed into the bottleneck. Cera used to let us in the Belgrade Cinema for free; calling us his little buddies. At the time, the cinema was usually empty, as all of Pula knew that, after eight o’clock, Cera tended to ‘mix up’ reels and show films from the middle or the end, or sometimes even backwards. But, his love of Istrian brandy, aside, Cera was one of the kindest people I knew. After he saw that none of us even remotely understood what the news was reporting that fateful day, he immediately turned to us and said, ‘The Slovenians can go swim their asses over to Luxembourg, if they don’t like it here in Yugoslavia.’

It was obvious that Cera’s ‘reels’ got mixed up much earlier than usual that day, so we continued to watch, astonished that this news hypnotized the crowd before us. We all believed that anything, even the ‘TV Calendar’ would be more interesting than the evening news, even though we didn’t understand a word they said. Sinisha and Mario suggested that we hit the road and head towards the apartment building, but I still had this idea that we’d find the guy with the lump, so I stepped forward to scour the crowd of ever more frenzied television viewers. Instead of our ‘watermelon man’ I saw, through the glass wall on the opposite side of the hall, none other than my father, slowly making

his way home.

His path home from work usually led him to the dormitory, where he stopped for a while for a beer or two and to hear the day’s news and its accompanying commentary, often in the company of his favourite, little Mirso. But that day, as Mirso stepped up onto a chair in front of the TV and addressed the gathered crowd with vigour, shouting ‘the time approaches when even the biggest of fools will learn a lesson or two,’ my father walked away thoughtfully, as if oblivious to what was happening only a few metres away from him.

I tried to muscle my way through the crowd and catch him in front of the entrance, on the far side of the building, but I quickly realized that jostling through this hand-waving mob would soon land me with a ‘labourer’s slap’ on the back, or the head. So I doubled back and decided to intercept my father in front of the shop. I could tell that he was dragging himself more slowly than usual, so there was no way he would get away from me. His gaze was empty, like a blind man’s, and I stood before the shop and watched as he approached. I felt like he was about to go past me, just as he had passed by the crowd in the dormitory. As my Aunt Enisa would have said, ‘He walked by without so much as a glance.’ But he did stop, eventually he did, and gave me a bear hug that nearly took my breath away, and under his uniform I could feel his abs, which the military had sculpted for him, and which he enjoyed showing off while wading through the shallows on beach holidays. Mother and I liked to tease him about that, and then he would divert us with some story about the difference in water and air temperature, and how it wasn’t healthy to dive into the sea. My father never drank at work, and I heard him say, countless times, that only in Yugoslavia would people drink more while at work than after work, and that this would send the country to an early grave. But that day he held me so powerfully in his muscled arms that I thought, in all seriousness, that he must be drunk.

He finally let go, but only to grab me by the arms a moment later, drawing me close and staring at me with an strange look in his eyes. After what felt like far too long, at the point when I thought he had finally lost it, he asked me if I’d like to go with him to the market and get a He-Man.

Such a suggestion could mean only one thing: something was horribly wrong. Action figures from my favourite cartoon were the best toys ever, but Mother had lain down the law and said that I couldn’t get any more, since I already had three from the series (He-Man, Skeletor and Tilo) and that, she said, was more than enough. She thought these action figures were way too expensive, and that I wouldn’t even play with them, since I was too old for that sort of toy. She also said that I only got them because I was spoiled. When she said this, she’d look at my father in a special way, and he would always pretend that he had no idea what she was talking about.

We walked in silence toward the market. My father didn’t stop every few metres to say hello to someone or go off for one of his ‘quick drinks’ with Vlatko or Mate, resulting in my having to carry the bag of shopping home myself. Such events would inevitably end in him stumbling home in the evening, giving my mother a drunken hug, a sort of dance in which she would scoot away, offended, then he’d hug her again, and promise there would be no more quick drinks next month. But that day, my father was strolling around Pula, his head bent low, hardly even nodding to the people he knew. What surprised me even more was that he didn’t want to stop at Nikola Tesla Park, where there was an old shack smothered in graffiti that read ‘Republic for Kosovo, Continent for Istria,’ and where we would almost ritually show up to count the gaggle of barefooted youths who multiplied every time. Father and I had taken to naming these kids ‘little Gypsies,’ because so many of them went swimming, every day, at the end of a long jetty wearing only T-shirts: just like Jovan’s son, Milan, a skinny teenager who, according to my mother, wore the shirt into the water in order to hide his prominent rib cage from the girls in class.

I never found out what the little Gypsies were hiding under their shirts, and I was never really interested, to be honest. My father, on the other hand, kind of adored the little Gypsies, and loved to say that he was one of them, especially when he was draining a bottle of his beloved Stanzec plum brandy. Then he would explain, in all seriousness, that when he had been no bigger than a bread loaf, his Gypsy parents, who had eighteen more little Gypsies to go along with him, had forgotten to take him with them, when they left the town of Futog, in Vojvodina, with their circus tents. By necessity, he had been adopted by a nice Serbian uncle, and an even nicer Hungarian aunt who, unfortunately, had died too early and wound up leaving him with the Yugoslav People’s Army when he was just a little boy. People used to listen attentively to my happily gregarious father, but never knew whether they should feel sorry for him, or envy him, for his life full of stories.

Regardless of whether or not my father had really been forgotten by Gypsy circus performers, or whether he had invented the story to gloss over a sad orphan childhood, raised by captains and corporals, it was nevertheless an indisputable fact that I was the proud owner of multiple He-Man action figures through the good graces of Maki, the Gypsy who sold them from one of the stalls. Father would haggle with him as long as it took, sometimes taking a good half hour to bring the price down from eight to four dinars. Only then, when Maki had accepted defeat and mumbled that four dinars was outright thievery, stealing from the mouths of the good people who smuggled the toys for him, would my father put ten dinars in Maki’s hand, pat him on the back, and say that he’d never met such an honest Gypsy in his life.

But there was no haggling that day. Father put the money in Maki’s hand without saying a word. Before I’d had a chance to glance over the shelves full of colourful junk, he had already disappeared into the crowd of Pula market. For the first time in my life, I was worried about my own father, and I began to push my way through the shoppers, almost in a panic. I had this idea that my father, lost in thought, would step out into the street without looking both ways, and some crazy Italian tourist, or an old drunk on a Vespa, would run him over. So I was running, action figure in hand, ever more nervous, bumping into ladies in floral dresses as I skittered through the market. My father was nowhere to be seen. It even occurred to me that he had forgotten we’d come together, and had headed home for lunch, when I finally saw him standing in front of the entrance to a department shop, looking confused. I was about to run to him when someone put their hand on my shoulder and rooted me to the spot. I turned around and saw Maki anxiously looking at me with his big black eyes. ‘Your old man is being very weird today. He wasn’t seconded, too, was he?’

I had never heard the word ‘seconded’ before and had no idea what it meant. I was eleven years old, and dreamed only of Mario borrowing his father’s boat and the three of us gliding off to a nearby island.

2

‘Republic for Kosovo, Continent for Istria’

I hadn’t a clue as to how this long-lost graffiti came to appear in Pula, but sixteen years later it seemed as though the letters beat a rhythm into my racing heart. Images, faces and places I had buried deep beneath the surface of my consciousness flashed before my eyes, like some strobe-lit MTV video. My past life flooded back like an hallucination, and I felt like I was on an uncontrollable merry-go-round which was about to catapult me into a world I’d long been convinced that I could block out. My turbulent, unrestrained subconscious shook itself loose and I surrendered to it, against my will. The bold black letters sprayed against the white walls of Pula flashed brighter and more vividly, as if they might explode with the cubes of stone on which they were painted. REPUBLIC FOR KOSOVO, CONTINENT FOR ISTRIA!

I sat in my twenty-year-old wreck of a car, parked in a garage next to the enormous brightly painted heating-plant in downtown Ljubljana. I should’ve driven straight over to Enes, my nearly legitimate mechanic, so that professional Bosnian clown could massage my car into shape for its first long-distance trip in many moons. But instead I just stared at the garage wall, where my illusions

were locked in combat. I tried to put my left leg into the car and press against the soft Japanese clutch, but my leg, as if it belonged to someone else, just lay on the concrete garage floor, disinterested in the rather important detail that Enes’ random working hours were probably winding to a close. For a moment I got worried that I would never be able to tear myself from this petrification of body and brain. I couldn’t recall the last time I thought about Pula, of those white officers’ apartment buildings and my childhood there before that summer of 1991. I’d buried them all in the ground one day, without bothering to mount a tombstone; without coffin, without grave candles, without eulogy or procession. Buried them and walked away, never looking back over my shoulder and convinced that this forgotten world would never burst from its grave and pursue me.

Motionless for what must have been over twenty minutes, I tried without success to return to the state of clinical mental lethargy; to that beloved indifference that had protected me for all these years, against the siege engines of emotion. But I couldn’t move, not an inch. My father, until recently deceased, assailed me now, sixteen years after his death, with an immortality so relentless that I could physically feel the sense of horror that grew inside me, nailing my feet to the ground.

Everything was flooding back: Pula and its graffiti, the Bristol Hotel in Belgrade, the unbearable humidity of Novi Sad. The image of Ljubljana was also coming back: the Ljubljana that once was. My mother, too, came back to me, as she was when she was still my mother. The festival of memories in my head played to its climax, and the great fireworks were about to begin. I gasped for air but couldn’t breathe; feeling I would surely faint.

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland