- Home

- Goran Vojnovic

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland Page 12

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland Read online

Page 12

Unfortunately, it never dawned on Dusha that what I needed was an ally, a friend, or a mother, much more than a well-intentioned immersion teacher of the Slovene language, who thought the most important thing was that I write imaginary essays and do my geography homework for school as soon as possible. She convinced herself that I would hit a language barrier unless she saved me by making up for having not spoken any Slovene for my first eleven years, and abruptly transforming me into her Slovenian child. Dusha believed that the correct use of the dual verb form, and a properly declined genitive, would provide an acceptable replacement for father, mother, friends, home and the sea. At least, that was how I saw it then. Now I’m closer to thinking that, in her own way, with love and a mother’s care, she was inviting me to finally move in to her Slovenian world, imagining that the successful transfer, or restart, would allow me to be a happy, cheerful boy again, as I had been in Pula. I was too young and sensitive not to resent this, and never admitted to her how badly I wanted to swim in this new ocean into which she had thrown me. I hid the fact that I watched Slovenian television, that I practiced repeating aloud the words of TV presenters and cartoon characters, that I absorbed the words of strangers in the lift, at shops and everywhere I could, to try to extract meaning without asking for it. I also hid how carefully I listened to her words, trying to understand and remember them.

I took great care to ensure that she never noted my interest. Whenever I heard the door unlocking, I switched the channel on the TV as a precaution, knowing that she would be encouraged and delighted by my voluntary viewing of a Slovenian programme, which would tip the scales in our duel to her side. Dusha probably never heard just how well I could say nasvidenje, ‘goodbye,’ when I left the lift after just a few days in our new flat. I was so proud of my second spoken Slovenian word that I was soon saying it, loud and clear. When riding in the lift, I began to look forward to using it, and was disappointed if I rode alone. I even began to wait intentionally in front of the empty lift, hoping someone would join me, just so I could say goodbye upon leaving.

Of course, not everyone in the area spoke Slovene. I’d say that the majority communicated in their mother tongues, fellow emigrants from elsewhere in what would soon be ex-Yugoslavia. Saying nasvidenje caused them much more trouble than it caused me, saying it all wrong, incomprehensibly, or not even trying to say it at all. During my early rides in the lift, which impressed me anyway because we hadn’t had one in our building in Pula, I heard some pretty funny variations on the word. I could catch them twisting their tongues around the simplest Slovene words, even people who were thirty, forty, fifty years old. Sometimes I felt sorry for them, but most of the time I’d nearly laugh. Every time I made a commitment that I would never be one of them, and that I’d be speaking Slovene sooner or later, so impeccably that no one would know where I had come from.

Our situation became more or less similar to our stay at the Bristol Hotel in Belgrade, only minus father’s late night phone calls, and with my mother going to work at the Polyclinic, rather than just for long walks. I didn’t know what she was doing, and was a little fuzzy on what a ‘Polyclinic’ was. I just thought it was the strange name of a Slovenian company, and she never bothered explaining it to a seemingly uninterested kid. If not for the inevitable approach of my first day of school, I’d have reverted again into the zone of that bearable temporariness of hotel room 211, where I’d waited for the world to start turning in the opposite direction, to return me to our flat in Pula and my friends.

My mother attentively watched the news every evening while I, with my back to the TV and seemingly engrossed in books or comics, eavesdropped on every word, trying to decipher the coded messages of adults in this foreign language. Evening after evening, my mother simply sighed deeply: her only audible reaction. The names of those on centre stage of this war remained the same, but they were accented differently from what I was used to. Every day it became less and less clear to me what was actually going on. I don’t know why, whether it was my mother’s sighs or the way the Slovenian newscasters sounded so serious, but I had the feeling that the war was getting worse and worse, rather than fading out. My fears for my father increased. His name was never mentioned on the news, and I had no idea if that was good or not.

In this mounting tension, co-created by the approach of school in this new environment, and my father’s disappearance, even my stalwart Podlogar stubbornness buckled for a moment, and I asked my mother, ‘When’s Dad going to come?’ To which she replied, probably in complete surprise and unpreparedness for my question, ‘You mean, ‘When is Father going to come?’’

Dusha tried to take her words back immediately and apologize, though without speaking a word, only with a gaze I pretended not to see and touches I shied from. Infinitely offended, I pulled away from her until I finally locked myself in the bathroom, where I made the definitive decision never to ask her anything about my father, ever again. Through the closed door, Dusha tried to explain something about how she didn’t know when it would all end, but she was sure he would come soon, that this was his job and that he would return when his job was done. She spoke Slovene and I could only guess at what she wanted to tell me so I started to yell and finally drowned her out, repeating: ‘I don’t understand you! I don’t understand you! I don’t understaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaandyouuuuuuuuuuuuuu!’ I screamed until she shut up, and defeated, slowly moved away from the door. I felt that we were moving away from each other forever.

13

Even after sixteen years in Ljubljana, returning to the town now felt like it had back then: buffeted by fierce, cold air that felt as if it was trying to chase you away. It was a town to which Dusha and I had retreated when we had nowhere else to go. Each time I drove out of Ljubljana and returned, I was hit by the same anxious feeling as I had that first time, the feeling that no one was expecting me here, no one here had missed me. I used to hope that maybe one day, after many years, I would get off the motorway toward the city and feel like I was returning home. But that has never happened. So tonight, at the first glance of the distant silhouette of the town I live in, I’m cast back to our lonely apartment.

This has always been a town better left to sleep during the night. But that night, rather than waking Nadia, I woke up the guy selling burek outside the train station, a poor soul that life chose to award with the task of serving fatty Albanian savoury pies to the drunken citizens of Ljubljana as they waited for the first night buses.

‘You want yogurt as well?

I nodded and, soon after eating the first piece of burek, I ordered another, which coaxed a barely-visible smile from my saviour. This was the indisputable climax of the communication between the Albanian slave and his customer. He was locked inside his kiosk, where laws that applied to those of us outside, on the road, did not reach. As I happily ploughed into my second burek, as I had many times before, I could only wonder if there was a way out of his kiosk-embowered existence.

It was the same guy, in the same kiosk, who had first welcomed me with burek when I celebrated my first pay cheque, and got drunk for the first time, aged sixteen. I found him there on the three or four occasions when I’d managed to come with drunken ex-girlfriends. He had been there for me when I foolishly lost a good job. But never, in all those years, had we been any more friendly than the exchange of silly smiles.

‘Hungry?’

I nodded, mouth full. Thus ended our communication.

‘Serbia! Serbia!’

‘We’re going for a burrrrrgeeeeeeeeeer! A Serbian burger!’

Three drunken guys on the other side of the road waved towards my kiosk-imprisoned companion, three fingers lifted high in the symbol of Serbian solidarity, and for some reason, in high spirits, considering their primitive provocations. They wore expensive clothes and found this awfully funny. Maybe they even thought that the burek guy was having fun too. But glazed in behind me, he only ga

ve them the same wan smile he’d given me. The smile that kept hidden the answer to the question of whether he’d only recently resigned himself to eternal live burial inside that aluminium kiosk, or if they’d prepared him for this fate as a child. I was sorry for him but, at the same time, he got on my nerves, because he refused to let me understand him. I suspect that he was incapable of seeing me as any different from the Serbian burger guys. We were all equally unimportant factors in his glazed life. I even thought for a moment that maybe he could hardly see out into the street, like suspects in a police line-up who can’t see the witness while he tries to recognize them. I looked straight at him once more, wanting to force some kind of reaction, make a deeper connection. But then it dawned on me that this man hadn’t done anything to deserve another provocation, so I withdrew my inquiring gaze. But the damage had already been done as he, out of learned caution, had already moved back and sat down on the stool in the corner of the kiosk, so that all I could see was a lock of his black hair peeking out from behind the counter.

Our story for that night had ended.

Despite the late hour, I was still afraid to go home and knock on Nadia’s door. I knew that I would be welcomed by her questioning eyes, expecting words that I still felt incapable of saying. So I went to the nearby platform, below the Stock Exchange building, where something vaguely resembling music emanated from a coffee shop. I thought I might have a coffee and settle my thoughts in a dark corner there, as I imagined whoever was inside would show no interest in me. I didn’t look dangerous enough for any stoned wimp to see me as a target for their inferiority complex, nor did I look like a helpless creature on whom some third-class hooligan might test new intimidation techniques. My dimensions were ideal for being ignored.

As I approached the bar, the undefined thumping sound slowly transformed into a deafening series of grunts. Inside I found a bunch of tracksuit-clad guys dancing by a table full of vodka-and-Red-Bulls, as well as the three Serbian burger guys. What little will I had to spend voluntary time with these unsavoury people vanished but, in a town suffering from traditional Central European exhaustion, the selection of night-life available didn’t offer much choice. I was aware that, no matter which of the two or three other night bars I might try, I would be equally bothered by the sub-cultural exhibits living it up inside. So I ordered two large beers and sat at an empty table in the corner, where I could observe how the Serbian music drove my fellow passengers on this night train into a pre-orgasmic state, while the sloppily-emptied ashtray on the table before me bounced and shook to the beat.

After the first beer, I decided that the hormonal deviants dancing nearby would not be sufficient to drive me off. I pulled a letter from my pocket, the one I’d found in Tomislav Zdravković’s apartment in Brčko, and read it again slowly, letter by letter, from beginning to end, knowing that I only did so out of desperation. The letter was my only remaining tie to my lost father, and I couldn’t accept the fact that it would bring me no closer to General Borojević.

As I reread it, I lingered over the name of Bojan Križaj. I remembered how Nedelko and I had cheered for him together and how, in the midst of the second run of a slalom race in Wengen, my father had even promised me, ‘if our Slovenian guy thrashes the Swedish guy today,’ he’d take me skiing to the Slovenian resort at Kranjska Gora the following winter.

Then I started reading it again. I was browsing, jumping from one end to the next until, at some point, just as the guys on the other side of the bar came up with the original idea of dancing on top of the table, I stopped short. I realized that another person I had ignored up until now actually appeared in the letter. ‘My darling, J. should soon set off,’ it said. The letter J indisputably marked someone who should have taken the letter to Dusha in Ljubljana.

While the drunken-howling idiots, spouting famous quotes from old Serbian films, could be heard from their tabletops, accompanied by hyena laughter, my heart started pounding more and more quickly, and my exhausted brain began to whir. I was thinking that, if she had wanted to tell me who her link to her ex-husband had been all those years, then Dusha would’ve already done so. So she either didn’t know who was represented by the letter J, or she was determined not to tell me. I was in the same boat either way. After our last meeting, at the Second Aid bar, Dusha was no longer available to chat about my father.

I had a second beer. It went down my throat faster than beer had in a long time, and I felt it would not be my last. After a long day’s drive, total exhaustion lurked beneath a crust of irritation. The first beer unlocked me, the second stoned me, while a third and fourth would’ve probably pushed me into dangerous territory, for my own health and those in my immediate vicinity.

‘Woohoo! Genius! Way to goooo!’

At that moment I looked around the room, because the waiter had cranked up the music, as per the request of the gentlemen dancing on tables. Further fuelled, two glasses crashed to the floor, as the table-dancers imitated a scene from a Serbian film, which had apparently intoxicated them more powerfully than the song to which they currently gyrated. At any other moment, this might’ve seemed funny to me, but that night they seemed as retarded as the music they danced to. They couldn’t have been more than sixteen, and were dancing to something that should probably look like a wedding party dance.

It was obvious that they belonged to a generation crazy about the idea of the Balkans, which at the same time managed to mix up everything completely: the good and the bad, the sane and the crazy, the banal and the evil. It was all the same to them. The only thing that mattered was that they were like people from the southern parts of ex-Yugo, that they dressed, spoke and partied like southerners. They couldn’t care less about war and war criminals. They couldn’t care less about anything in this world.

‘Just turn it up and rock!’

I got up, walked to the bar and ordered another beer. But in order to pull this off, I had to drown out the vocals. So I shouted to the waiter to turn down the music and, to my surprise, he did.

‘Another bee... ’

‘Hey! Hellooooo!’

I turned around and saw an overly proud representative of the sixteenth generation of immigrants standing before me, or I should say many inches below me. He appeared determined to prove his Balkan temperament in front of his friends, and live up to the genetic intricacies of his great-great-grandmother, who was doubtless a renowned brawler. He held his glass in his hand in such a way that I was meant to believe he was about to smash it over my head.

‘Who allowed that, huh?’

Two large beers had intoxicated me just enough to have no remaining tolerance for teenagers who wanted to measure their dicks against mine. So as soon as this kid brushed against me, everything went black and I pushed him back with all my strength, so that he toppled back and fell over a chair, onto the floor.

‘Why don’t you go fuck yourself!?’

The moment I said those words, everything around me stopped. I put these guys on mute and stared absentmindedly in front of me. This was Nedelko’s favourite curse, and it had flown out of my mouth as if he had spoken from within me. After all these years, I heard him speak again, and suddenly, I could see him, holding my hand tight, arguing with the guy at the entrance to the Arena theatre.

It was at the Pula Film Festival when, in the middle of the film Volunteers, my constant laughter made me urgently want to go to the toilet. But despite Nedelko convincing me to go, I really wanted to see the film all the way through, fearing I would miss one of the funniest bits. As the film’s cast and crew took their post-showing bows on stage and Nedelko realized, with some disappointment, that his favourite Yugoslav actor wasn’t among them, we finally made our hasty way to the toilet, but a long line of people, each shifting from one foot to the other, had got there first. I just couldn’t wait any longer. At first, Nedelko tried to c

onvince me to take a splash right there, in the darkness, reasoning that I was just a kid, and kids can get away with anything. But I heard my mother’s voice inside my head, saying that only Bosnian scum pissed around the Arena. So Nedelko had no choice but to quickly take me to the nearest bar, where we managed to push our way to a free urinal, a second or two before it would’ve been too late.

But then they wouldn’t let us back in the Arena to see the next film, which was about to start. Old habits die hard, and Nedelko had crumpled the tickets to the first screening in his pocket without realizing it, and had thrown them to the floor. The young man at the door insisted that anyone could come up with the slipping-out-to-piss story, though I doubted there were many other people who would smuggle themselves into the Arena at midnight with an eight-year-old in tow. Increasingly nervous, Nedelko initially focused on attempts at diplomacy, and patiently tried to convince the young man of our innocence. Then I noticed that the film had already begun inside. That’s when he lost his temper. For the first and last time in my presence, everything went so black before his eyes that he raged like a beast at this young man, punctuating the outburst with his favourite six-word curse. Then he was instantly calm, and took me past the petrified ticket-tearer, straight to the Arena, where our empty seats awaited us.

I could no longer remember the second film we saw that night, but I certainly saw and heard Nedelko, as vividly as if it were yesterday, shouting ‘Why don’t you go fuck yourself’ just like I had, so that all the energy amassed in the one-syllable ‘go,’ and the rest of the phrase was an echo articulated at a slower cadence. This allowed the word ‘fuck,’ towards the end, to go on and on, while the emotional charge moves toward the threatening gaze, which finally slays the interlocutor, after the beginning of this perfect curse has paralyzed them with its sharpness.

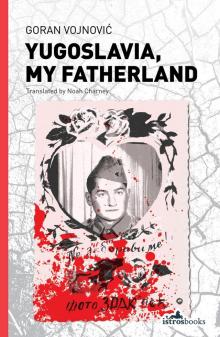

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland