- Home

- Goran Vojnovic

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland Page 16

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland Read online

Page 16

‘I can still hear this question, so trivial, so stupid and so painful. He accepted our departure so humbly, just like he had accepted the war and his role in it. I decided, at that point, that this was the last time he would hurt me, so I just told him not to call me again, and that I didn’t want to hear about him anymore. And he just went: ‘Okay.’ Okay! Okay?! He was tearing me apart alive and I could’ve screamed, kicked, banged my head against the wall, but I couldn’t do anything in that apartment full of his relatives. I wanted to kill him, to knock him down with my bare hands. Okay?! He said ‘okay’ and went quiet again. I probably didn’t realize that he was intentionally pushing me away from him, pushing us away from that place. Of course, I couldn’t know everything he knew, and I couldn’t understand what was really happening with him, around him. But I especially couldn’t, and wouldn’t, understand his resignation and his helplessness, and even today, I can’t understand that. His reconciliation with the fact that he had renounced the fight for his own life, as if it meant nothing to him. It hurt that he gave up on me, but I couldn’t accept the fact that he gave up on you too – his only son. And I couldn’t forgive him for that. I wanted to punish him for that, to call him monstrous, cruel and insensitive. And then I told him that I’d go to Slovenia, and that I’d tell you that he’d died and that he’d never see you again. And he replied: ‘Maybe it’s really better this way.’ I couldn’t believe those words; I didn’t want to understand them. I didn’t want to know that there really was a reason in this world for a man to wish himself dead in his own son’s eyes. I didn’t dare think about what that reason could be, what could be so horrible, so awful. I was sure that he was exaggerating, that he was dramatizing, as men do. Look, it still gives me the creeps thinking about his words, but back then I was shaking so badly that I could barely hold the receiver in my hand. You know, I wasn’t even serious I only wanted it to hurt him like it hurt me. I wanted to hurt him so he would bleed a little. But he just accepted his own death.’

‘I thought to myself, this is no longer the man I married. Someone else was calling me, pretending to be him. Someone was taking me for a fool, intentionally bullying me. Because I didn’t recognize him anymore. Maybe if I could have seen him once more, if I could have looked him in the eye once more, if I could have touched him. I don’t know, maybe I would have felt differently, but this way I had a feeling that I was leaving a mad stranger, a weird, foreign voice, which spoke only vague and illogical things. Otherwise, I would have probably never plucked up the courage to sit on that bus. Otherwise, I wouldn’t dare turn up outside my parent’s home.’

‘But despite all that, as you know, I couldn’t bury him right away. At first, I just left and broke off contact with him. I thought this would be enough for him to understand how far he had driven me, how far away from him he had driven me, so far that I knocked on Dushan Podlogar’s door. Nedelko was the only one who knew how hard that was for me, how humiliating, how unbearable it was to see that man’s hidden satisfaction again, and Maria’s sleazy submissiveness.’

‘After all that, it was a hundred times worse than ever before. I could only hate them even more for everything. I couldn’t have any understanding for anyone, least of all for them; with their reproachful eyes... every hour spent in that house was hell for me. They never asked where my husband was, and what had happened to him, or if everything was okay. He could have been dead, but they weren’t interested at all. They weren’t interested in me. It seemed to me that Dushan accepted you only to show me how very wrong everything in my life was. When you’re as desperate as I was back then, in that house, everything tells you that the world has conspired against you. I knew that we had to run away from there, too, because my home life continued right where it had once ended.’

‘Yes, Vladan, in the meantime, while I was running around, I forgot about you. I forgot, I know. And I feel awful about that. I forgot about you, Vladan. I know that now. I know that I left you behind, even though you were holding my hand all the time, and running around that mad world, right behind me. You were a part of that life, I couldn’t help myself, and you don’t know how very sorry I am, but you were, for me you were, the life I was running away from. I know that now. But then I felt I had to end that story, otherwise I would just die. I couldn’t be a part of that story on the other side of the phone line. I felt like it was all over, that we didn’t exist anymore, that there was no Pula and no Borojević family anymore, and I wanted to go on. Elsewhere. Anywhere. Just without Nedelko.’

‘But he started calling again. He wanted to hear how the normal world sounded. He began pretending that everything was as it had been, asking me all sorts of foolish things, about shops, the neighbours, the weather, all this nonsense. I was going crazy, and he wanted to hear what we’d had for lunch. I thought he’d lost it. Thinking about it now, he probably needed this impression of reality for a few minutes, an audible image of the world where people still went to supermarkets and cooked lunch. Maybe he tried to stay composed, but he seemed more psychopathic by the day. I know I was horrible to him then, I told him all sorts of stuff, but that was how he appeared to me.’

‘I began to grow afraid of him, I was afraid of his calm voice and questions about what we had watched on TV. You know, we never, not even once, spoke about the war. Never. Not a word. He didn’t try to explain anything to me. And I never asked him anything. Sometimes I tried to imagine a colonel who was calling his wife from the battlefield, after a bloody battle which left scores of young boys dead, talking to her about finding a job, about the price of rent, about painting walls. And I saw this madman in front of my eyes, and he didn’t even resemble the man I had once loved more than anything in this world. And I was more and more certain that I didn’t want to have anything to do with this man I imagined standing on the other side of the phone line. And I especially didn’t want you to have anything to do with him. I resented talking to him more with each call, and I was closer to breaking off contact.’

‘At some point, I don’t know what he said, maybe there was just too much of everything, I knew that I didn’t want to ever see him again, and what’s more, I didn’t want you to ever see him again. I couldn’t explain this to myself then, I still can’t, but I can’t regret it, either. I still feel it was the right thing to do. You should have heard him; then you’d know what I’m talking about, understand me. I had to tell you that he was dead. I had to bury him. If you could only hear one of those numerous conversations about nothing, if you could only hear his calm voice, you’d know that I had no choice. I had to. Because of you. I had to bury him...’

Dusha kept talking, carrying on with her story, but I could only hear that one non Slovenian word she said to me during our life in Ljubljana. I watched her lips move, still telling her story, so long-delayed, explaining it to me. I watched her finally open up to me after all those wasted years, but I could only hear her distant voice repeating a single word:

‘Dead! Dead! Dead!’

18

‘Dead!’ she said again, after I hadn’t responded to her sudden pronouncement: ‘Dad’s dead.’ As always, I replied to her Slovene words with silence. Maybe she realized that, this time, it wasn’t so much an example of incomprehension as rebellion. Or she wasn’t ready for this situation that she had doubtless rehearsed in her head over the course of months, and so she translated herself instinctively, as if by mistake, for the first and the last time, into the discarded language of her long-dead happiness. Anyway, my mother told me the most shocking news a twelve year old can imagine, and did so in two languages.

Earlier that cold February day, she had bought me a football, which she called a belated gift for all our missed holidays, and had literally forced me to go out to the icy school playground to play with it. There, completely alone, in gloves and a winter jacket, in my guise as the loneliest orphan in the world, I had absentmindedly set about beating an invisible goalkeeper. Empty tarmac platforms, desola

te since mid October, gaped around me, as I kicked my new ball, a gift I hadn’t dared wish for, because I had known we didn’t have the money for it. I had suspected that this was her desperate attempt to get me away from the apartment for some reason or other, or to try to help me, in her own way, to fit in with my peers in front of the apartment building. I had even thought that this might be a flash of her maternal instinct, once considered extinct, but I certainly hadn’t thought that it was a way to cheer me up before ruining my day, my week, my year, my life.

So, at minus three degrees Celsius, I had been kicking my new ball around, hands jammed into my pockets, feeling endlessly sorry for this woman who didn’t know how to get close to her child, and ended up buying him a football and sending him into the bitter cold, as part of her master plan to cheer him up a bit. I had even become aware of her irreversibly mislaid sense of reality, her lack of realization that in February sport fields were empty, and shooting at goals in winter boots was no fun at all. I had felt sorry for the woman who, wishing to make her son happy, made a fool out of him.

After less than an hour, I had returned from the field and found her with a tear stained face, which only confirmed my premonition. She didn’t wait for me to take my boots off, for my hands to thaw and for my cheeks to regain their colour. She didn’t wait for me to unwrap my scarf and take the cap off my head, but she just shot:

‘Dad’s dead!’ and then, in case I missed it, ‘Dead!’

I didn’t respond and my face remained unchanged, while Dusha started explaining how he had died. I remember words just pouring out of her, but I wasn’t listening and went to my room, pulled Hashim’s still-intact packet of green firecrackers from under the mattress, and ran back outside. She yelled after me, called for me to come back, but at that moment, I only wanted the world to start cracking. It had to crack, that was all. I felt nothing else.

I think she ran after me, but I was too quick for her, and raced towards the pitch, which was still desolate and easily provided shelter to hide from anyone who could have peeked into my mourning ritual. There were a hundred firecrackers in the packet, a hundred powerful green firecrackers that echoed around the neighbourhood, one after another, as I sat under a tree by the playground, lighting them up and throwing them, my mind a blank. It was cracking, it was really exploding, and it took a nice long time, as some firecrackers were really hard to light up, but I didn’t mind it at all. The lighter I had almost pulled from Dusha’s hands burnt my fingers, but I couldn’t have cared less. I felt the need for it to crack and burst and boom and I wanted never to run out of firecrackers; for them to crack more and more powerfully, as I lit them up more quickly.

I had about ten unlit firecrackers left, when two police officers approached me, pulled me roughly up to my feet, walked me to their car, and drove me straight to the police station. They asked me where I lived, and what my name was. They wanted the phone number of my house, the name of my father and mother, and a hundred other pieces of personal information that I obediently gave them, hoping they would never ask me why exactly I had been sitting there under a tree throwing ninety firecrackers.

I don’t know if Dusha already explained to the police officers over the phone what exactly had happened, but when she got to the police station, she didn’t say a word. She just hugged me and kindly nodded to them. She was probably incapable of speaking, because she didn’t say anything when we got home, either. In the evening, she tried once more to tell me about Nedelko’s death, and also to comfort me, but I wasn’t listening and just let her hug me, thinking that I was comforting her, too. The next morning, we both pretended that we woke to a completely normal day, and didn’t speak about firecrackers, police or deceased fathers. According to my mother, Nedelko Borojević died on 17 February 1992. And that was it.

19

Dusha’s story returned me to a place I hadn’t visited for a long time. I had suppressed the time of Nedelko’s death, and for years that ice cold February day didn’t exist for me. My father had to stay buried deep within me, because he had no other grave, and his death had to remain unreachable to all my everyday thoughts and feelings. Emma, one of my first girlfriends in secondary school, was the only one who managed to pry the information out of me that my dead father didn’t have a grave. She asked me several times how I could live with that. She was telling me about her grandmother, who was left without a brother and father after WWII and who, for over fifty years, yearned for a grave at which she could kneel, light a small white candle; a place to pray at and silently say their names. I kept claiming that I didn’t need my father’s grave, that my father was dead and that his story was finished for me.

So Dusha returned me to where many people keep returning, but from where I had once fled, in order to escape my sadness. As I listened to her tell me about those difficult times, I kept returning to that tree beside the football field, lighting those green firecrackers, one after another, which cracked closer and closer to my legs, until I started putting them on the ground right next to me. If I had had more firecrackers back then, and they would have let me throw them all, I thought, they would have started cracking in my lap and in my hands, sooner or later. I had been driving pain away and at the same time, calling it back. In the end, the part of me that hadn’t wanted to grieve, that had resisted the pain, had probably won.

But now Dusha also woke that other, more sensitive and vulnerable part of me, and I sat there next to her, incapable of responding to her words. She returned me to the foot of that tree by the icy football field, and it all began all over again. Only that this time my father didn’t really die, I just felt like he had died. Died daily, for sixteen years.

I pulled Nedelko’s letter from my pocket and pushed it into her hands.

‘Where did you get that?’

‘From Brčko.’

She took it and started reading. I watched her face carefully, but couldn’t tell anything from it.

‘Who is J?’

‘How am I supposed to know that?’

‘Wasn’t he bringing you his letters?’

‘No. Nobody was bringing me his letters. The letters came by post, and were sent from Slovenia. In ordinary white envelopes, bought and sent from here. Without a name or address. I never knew who was sending them. I thought it was better that way.’

I don’t know if my helplessness really touched Dusha, but I had a feeling that she was apologizing to me, and that she was genuinely sorry that she couldn’t help me.

‘Maybe...’

‘What?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Tell me!’

‘Maybe Brane might know something. I can ask him to meet you.’

Brane was Lieutenant Branko Stanežič, who used to come to Pula for holidays every summer, and had brought father his plum brandy. Back then he was General Stanežič, the man Dusha had hoped would help her find a job when we came to Ljubljana, but she couldn’t get a hold of him. Although she called him at home and at work, and although even I sometimes spent afternoons by the phone, incessantly dialling his work number, nobody ever answered. In the end, he was just Mr. Stanežič, who began to appear on TV, and replaced his military uniform with a nice blue suit. Soon after that, Dusha finally gave up on him, and I was set free from my redialling duties.

At that time, Mr. Stanežič became an overnight star of round tables and TV panels, and journalists addressed him with visible awe, even though the titles written under his name grew more indefinite by the year, as did his words. At least that was how it appeared to me, trying to see in him the Brane who used to barbecue on the beach with Emir and Nedelko, and fall asleep in the sun after lunch while I, together with his sons, had to move him into the shade, so that he didn’t get burnt. I wanted to recognize the person in him who put on his younger son’s yellow snorkel mask, and gathered tiny shells for hours on end, while his ‘white as that Italian cheese’ butt stuck out of the wa

ter; the guy who made us all sing Partisan songs in the evening, before he finally passed out drunk, and Emir and Nedelko took him to his Lada, which we then towed back to Pula, because his wife didn’t have a driver’s license.

But regardless of the effort I put in, I just couldn’t see that funny quasi-uncle in Mr. Stanežič, who liked so much to talk about social changes and democracy, and thanks to whom I still sing ‘Through Valleys and Over Hills’ with a Slovenian accent. Brane was Mr. Stanežič, even when he unexpectedly turned up in the final act of the disintegration of my family, which began exactly the way a tragicomic Balkan story should; with a wedding.

While in all other circumstances it was forbidden, traditional weddings brimmed with men’s overtly-expressed emotions, disastrous hairdos, poorly-tailored cheap suits, awkwardly-tied ties and background music, which was probably used to keep uninvited busybodies at bay. It was a typical Serbian suburb wedding, where a God-forsaken Serbian village moves for the day to Slovenian tarmac and settles among apartment buildings to suitably celebrate the wedding of its ‘son/brother/grandson/nephew/cousin/neighbour’s Slovenian best pal, Dragan’ who, for this occasion, ‘fuck it, found a Slovenian girl, but fuck it, may he be happy and live long and healthy.’

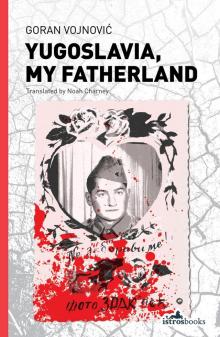

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland