- Home

- Goran Vojnovic

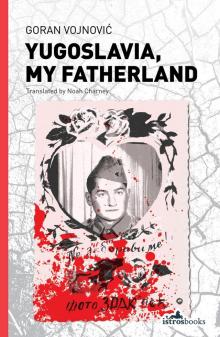

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland Page 23

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland Read online

Page 23

I was ashamed because I wanted to believe this story the whole time, which was probably at least partly made-up to defend a war criminal to me. I was ashamed because I silently wanted for this story to be true, from the first letter to the last, ashamed because I had subconsciously longed for the understanding and justification of my father from the very beginning.

This was the sin that lay on my consciousness that morning. At some point, I had subconsciously stepped onto his side, and I was willing to believe in his fate. In bodies stacked in piles, hidden truths, concealed heart stopping pain, latent fury that can turn a man into an animal... I was willing to believe all of this.

I was ashamed of this belief, and even more ashamed of the naivety and unawareness that its greatest believer had been telling me this same story, all this time. A believer who wanted to present himself as the greatest victim of this story, and who expected me to complaisantly nod and unconditionally accept all the aforementioned, just like I had done. I was appalled at myself, disappointed that I let myself be enticed and misled by him so easily, that I got caught in the trap he’d set up for me.

My nausea was getting worse, and I finally had to move. Nadia didn’t say anything, only stroked my back while I was getting up. In the bathroom, I pushed my head under cold water in the sink without hesitation, and let the water run down my neck and flow to the floor. Then I was drinking it, gulping it, and hoping it would put me out of my misery, at least for a second. It didn’t help. I took my clothes off and stepped into the bathtub. My exhausted body couldn’t stand up straight anymore, so I sat down and just let water fall all over me. I pushed my foot in the drain to stop it from flowing out, and then watched the surface slowly rising.

But the sense of shame wasn’t vanishing, and I felt like a part of me was ashamed of my own attitude to this lost father, of the fact that I resisted being on his side with all my might, that I’d looked him in the eyes (my eyes) and had rejected him. I rejected the man who had been the centre of my world for eleven years and who, in his own way, was apologizing to me last night for everything that had happened to him since those eleven years finished. This man eternally trapped in the body of a war criminal, who in the end, only wished for me to believe the story he was telling me. But I didn’t want to believe anyone or anything.

I heard a gentle knock on the door.

‘Vladan, are you okay?’

‘I will be.’

I didn’t have any intention of moving from my temporary position. I still had to sort out so many thoughts in my crazed head. Thoughts about him: Now evading me, and running back into the unknown.

Yesterday I thought I knew everything about the man who used to be my father. But now I only knew that I didn’t know the first thing about him. Last night everything was scattered back into doubts and questions. I went back to the beginning of this story and again, I could only see Nedelko’s empty gaze on the day my childhood had ended. Did this man live after that day at all, or was it him who was carrying his name? Was the man who sat with me at the same table last night at the Stomach Restaurant the same man who had taken me to the market in Pula on that distant hot June day, and bought me his last gift?

All the same questions were popping up again. And, again, I didn’t have any answers. I was sitting in the bathtub, locked in the bathroom of a hotel room at the Wild Pension in Vienna, pushing my head between my knees and staring at the cold water gathering around my feet. I shivered with cold, but it was easier to put up with the cold than the pain that merely subsided and waited for me to step back out into today’s morning, back into the first day of my new life.

A few minutes later, I saw Nadia in front of the bathroom door, holding two aspirins in her hand.

‘Take them.’

I did as she said and went back to the bathroom to down the pills with water. Then I went back out and lay on the bed. I had a feeling that the world under my feet still hadn’t settled, and that it was still restlessly swaying. Nadia sat down next to me and put her hand on my chest.

‘Do you want to get some breakfast?’

‘No.’

‘How about a walk? Maybe fresh air would do you some good.’

I shook my head. All I needed at that moment was somebody to listen to me. For the first time in my life, I felt the physical need to shake out all the amassed bitterness pounding inside my chest beneath Nadia’s hand. I had to get last night out of me, word by word: I had to spit it out.

So finally, hurt and not completely devoid of cynicism, I began telling Nadia about the bloodthirsty executioner who had convinced himself that he was just an innocent victim of fate. About a criminal who wanted to make me believe in his innocence, and had almost succeeded, because it was so tempting to buy a story that transferred all responsibility on to something so intangible, invisible and almighty as ‘fate’. I told her about Nedelko’s faith in it, about his faith as his redemption, in the same manner as all other faiths that helped people face whatever they couldn’t face themselves. Death, for example, and even more, sin. I confided in her that I thought that Nedelko’s fate was his God. Nedelko, I said, became just another believer at the hands of the Almighty, who led him on and who would forgive all his sins in the end.

‘If his faith was as firm as you say, he wouldn’t need you to confirm it for him.’

‘On the contrary. It is difficult to firmly believe without help.’

I also told her about the farewell he had predicted. I tried to convince Nadia, and myself even more, that it was just about enticing my pity, that is was a game which Nedelko had decided to play last night, but she just shook her head.

‘Maybe he called you just to help him die in peace.’

These were words I didn’t dare say, even though they were constantly on my mind. I was too afraid to admit such a role was being assigned to me last night. I was afraid of the realization that Nedelko had been looking to me as someone who would reinforce his belief that he was just a tiny, helpless marionette on the great string of history. I was afraid of the realization that he had wanted my understanding only to finally justify himself to himself, to calm him down and satisfy him and prepare him for death. The death he had forecasted to me.

‘And if I understand correctly, you didn’t help him do that last night. Quite the opposite.’

‘Is it okay to help a war criminal die in peace? Even though this war criminal is your father?’

Nadia finally helped me, maybe even without knowing it, arrive at the question that had been haunting me this whole time. It only had to be articulated. But she was silent, as if she had wanted to tell me that I was the only one who could ask himself such a question. And that I was the only one who could answer it.

The train was slowly carrying us towards home, and returning us to our everyday life. Her to her microbiology; me to my coffee vending machines and occasional lectures. We were again threatened with the normal life that we hadn’t known how to live before going to Vienna, and that would test us all over again. We sat opposite each other, and I could feel that both our minds were wandering toward tomorrows, when we’d be alone again, and have to fight the silence between us. I felt Nadia asking herself if this train wasn’t returning us to the place she’d wanted to escape so badly, the place where she’d tried to talk to me in vain.

‘Vladan... ’

This was the ‘Vladan’ that didn’t promise anything good, the ‘Vladan’ that scared me, the ‘Vladan’ after which something was ending.

‘I was thinking... I decided to go back to my parent’s house. At least for a while. All this... the thing with your father... this was too much for me. I hope you understand. Maybe we could... after we take a break from everything... I want us to start again. From scratch. Not immediately, but after everything settles down. When you’ve resolved... when I’ve resolved everything. Maybe we could try

again. If it works out. But now I’d like to go home for a while.’

Instead of answering, I began to guess which of the many silences had killed our story. I was toying with turning back time, and imagining how it would have ended if everything that did happen, hadn’t. But I didn’t object because, after everything she’d done for me, I didn’t have the heart to convince her to sacrifice herself for me some more. For us. Even though I wanted to more than anything, and I was scared to death of being left without her. Nadia was looking through the window and crying, and I wished I could cry with her. To show her I cared, to show her my gratitude, my commitment. At that point, I realized that I had never loved anyone as much as I loved her, and I was determined not to let her disappear from my life, like I had with everybody I had loved before her. I’ll let her go, but I won’t let her stay away.

I was telling myself this, and yet I didn’t believe it. I didn’t believe that I could bring her back into my life. My fear grew and I panicked again. After Nadia, I couldn’t see anything, because after Nadia there wasn’t anything. I wanted to at least thank her, thank her for everything she had done for me. Or at least to apologize. Tell her that I understood, that I knew that she was too young, that I knew that she was just a kid who needed attention and love. But instead, I let us drown in our last silence.

27

After a long time, I awake alone in my bed, and find myself in this blinding and deafening emptiness, which pushes me away from my own thoughts as I try in vain to compose them. I feel like I’ve just emerged into this world, without memories and impressions. Everything is new, but I lay here without expectations, without desires and without any longing to discover what might await me. My town no longer extends beyond the walls of the room. For me, there is only an even larger emptiness than the one I’m stuck in now.

I’d thought countless times about leaving and now, with Nadia no longer by my side, I realize that nothing except fear of other foreign cities is keeping me in Ljubljana. I’ve been afraid of the realization that all the cities in this world are equally foreign, and that the same people walk everywhere. People you can never really know, just as I’ve never known them in this town. For me, Ljubljana has always been, and remains, the town of vaguely familiar foreigners. Here, where my home is supposed to be, nobody misses me. The best witness of this is my phone, which hasn’t rung for the four days and five nights that have passed since Nadia’s last call.

Nadia and I have occasionally spoken on the phone. These have seemingly been conversations about exams, about her home life, about coffee machines, about the weather, about everything and nothing, conversations in which the unspoken has out-shouted the spoken. Nadia hasn’t said anything about our relationship being irrevocably over, and I’ve never told her how much I want her to come back to me. I know my story frightened her, but I also know that I couldn’t comfort her and that, with me, her fear would only grow.

I’m not the kind of person who forms bonds with people. Everybody, slowly and invisibly, has drifted away from me until they ultimately leave me altogether. But still I’ve never felt so abandoned by anyone as I feel abandoned by her. Nadia came close to me, close like nobody before her, but I don’t know how to show her this. And I know even less how to tell her this, and with every broken past relationship, the burden of the unspoken only grows heavier and more unbearable. So I stopped calling her, and I know that soon she’ll stop calling me, too. In the end, you can overcome everything, but you can’t overcome yourself. I’m beginning to believe that each of us is destined to be themselves, and that is all.

Since I got back from Vienna, I often compare myself to Nedelko, recognize myself in him and him in me, and more and more often I think about how similar we are. He was a runaway war criminal and I was an abandoned hero, but I’m overcome by the feeling that my life has punished me the same way his life has punished him. We were both hiding from people, and are caught in the dark mazes of our inner worlds, as if we had both been serving the same sentence. I thought countless times that his crime was my crime, and am slowly accepting it, like I’ve been accepting everything life has brought me over the years.

I return to Tomislav Zdravković’s apartment in Brčko every day, and feel like somebody has locked me in there and forgotten about me. I sense that Tomislav’s great loneliness has swallowed me. I used to be sure that only people chased by great sins, like Nedelko’s, could tumble down into this loneliness. But now, as I wander around Nedelko’s empty hideaway, and look in vain for an exit, I realize that this loneliness is the most devastating legacy, and that it is slowly becoming the loneliness of all of us who remain behind after they are gone, and dream about our own innocence.

One morning I am awakened from this loneliness by Dusha.

‘Vladan, have you heard?’

It’s like I’m getting a call from a Dusha of the distant past. Her voice is the voice of my mother. Not only because of her use of Serbo-Croatian this time, but also because there’s something in this voice that sounds like she is calling me from my non-existent memories, as if Dusha has become my mother again.

‘No. What is it?’

‘Nedelko... he killed himself... They said... They found him... this morning... dead in Vienna.’

Nedelko flashes before my eyes for a second, but disappears again immediately, and everything vanishes. I start running my hand over the bed, as if I want to make sure that the world is still where I’d left it.

‘Hello, Vladan, can you hear me? They told me... ’

‘I heard.’

Dusha goes quiet. I realize that she doesn’t know what to say. When Nedelko died for the first time, she didn’t say anything. But then I hear those short trembling breaths, revealing a person who is about to cry. It dawns on me that, for her, this is his first death, and that she can’t overlook it the way she had overlooked it when Nedelko had died for me alone.

I realize that Dusha secretly loved Nedelko in her own way, maybe even as powerfully as when he was waiting for her with a rose in his cut-up palm, on Platform 2 of Pula railway station. Suddenly, listening to her cry over the phone, I feel sorry for her; sorry for my mother who isn’t allowed to mourn his death in front of anyone except me; sorry for her because only now can she begin her new life; that only now, when so much has irreversibly passed, can she really start her life with Dragan and Mladen.

So, in a strange way, I experience her call as our farewell. When she runs out of tears, the last invisible tie between us, which has separated and connected us for years, will be broken, and we will finally be severed. We will finally live in parallel, mutually untouchable worlds and we will be able to spare each other pain. When she runs out of tears, this will be the end for us, and we won’t look back. Goodbye, she’ll say, goodbye, I’ll say, and this will be the end, once and for all, of a seventeen year game that not only took away my father, but also took away my mother. When she runs out of tears, this will be the end, once and for all, of the Borojević family.

At that moment, I suddenly hear Loza, Emir Muzirović, yelling with his Bosnian accent, ‘Fuck Yugoslavia and God!’ and I see myself in a vague mist, silently asking my mother what the word ‘andgod’ means, and then I see Dusha explaining to me that this is probably a word we inherited from Turkish, and that we would learn about these left-over Ottoman words when we read about the Bosnian Nobel laureate, Ivo Andrić, at school.

Next to us sit three former friends, Nedelko, Emir and Brane. After a missed penalty kick by Faruk Hadžibegić, in the quarter-finals of a world championship, they sit in front of the TV, as if they’ve been waiting for the match to continue, and for Yugoslavs to get another chance.

‘That’s our character for you and one day that will fuck us up. He could’ve spat on anyone he wanted, he could’ve spat on Burruchaga from head to toe, like our Refik did at the World Cup, and the ref would’ve pretended not to se

e. But he had to spit on Maradona. Because Burruchaga can get spat on by anyone, but only he, Refik Šabanadžović, the Bosnian motherfucker, can spit on Maradona!’ I hear Emir yell.

‘I would’ve understood if he’d spat on Tito’s picture, but not on Maradona. That’s like spitting on football, like... like spitting on God, fucking God and his father!’

His voice keeps echoing in my head, and I stare at Nedelko, as he pours another glass of plum schnapps, saying: ‘That’s us for you, Loza. We spit on God and then it backfires and we’re surprised.’ I stare at his teary eyes and hear Dusha say the very thing she shouldn’t at that moment: ‘When’s the next championship?’

‘What championship?! There’s no championship anymore! It’s oveeeeeerrrr!’ Nedelko screams inside my head, and even Emir is quiet in the living room, staring at his compadre, while Brane Stanežič catapults from the armchair, so that I can distinctly see him wipe away his last Yugoslav tears. While my mother is gently leaning a glass against her lips, approaching my father and gently hugging him. And he, not trying to resist her, wraps his hands around her, and presses her head firmly against his chest. Now I see my mother indicating that I should come closer, and father letting me join their embrace, so that soon his strong hands clutch me.

So there we stand, the three of us, squeezed against each other, and father is squeezing mother and I more and more powerfully, kissing us in turns, and I, with my head against his chest, am listening to his heartbeat. Ba boom. Ba boom. Ba boom. Ba boom. Ba boom. Ba boom.

The remote, faded image of three people hugging in our apartment in Pula grows more and more powerful, more and more vivid, and I suddenly feel someone squeezing me, leaning my head against their chest, so I can hardly breathe that hot air trapped between the hugging bodies.

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland