- Home

- Goran Vojnovic

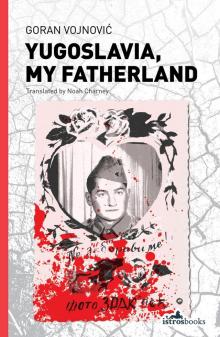

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland Page 24

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland Read online

Page 24

I try to pull myself away from this stifling image in my head, and start carefully listening to Dusha’s sobbing again.

‘Vla... ’

‘Yes.’

Her breath gets longer and deeper, and everything becomes quieter, until my mother, on the other side of the phone line, becomes completely inaudible, and I don’t know if she hung up, or she finally ran out of tears.

28

‘I’ve already fulfilled his last wish and everything’s waiting for him. Just like he’d wanted.’

As I walk among the graves at the famous naval cemetery in Pula, looking for the name of Tomislav Zdravković, the name that hid my father from the truth about his crimes for the last time, Loza’s words are getting louder and louder. I don’t pose any questions to the man who had called me to tell me that my father was buried here, at this cemetery, but I’m sure that this was the last wish fulfilled by Captain Emir Muzirović for Nedelko Borojević.

After burying his friend, whom he had helped hide from The Hague Tribunal for so many years, at a memorial cemetery protected by The Hague Convention, Loza also died. At least the papers said that he died, but I know he killed himself. But that’s not important anymore because, thanks to him, Tomislav Zdravković now lies here somewhere, a place where no one should search for eternal peace, but which might be the only correct place for him. Here somewhere, among soldiers of countless armies, with the souls of their countless victims watching over them, while the non-peaceful await their oblivion and the final forgiveness of history.

An invisible force is dragging me today, towards the grave of August Rittera von Trapp and Hedwiga Wepler, and only when I stop in front of it, do I realize that I have already stood here once, with him. ‘Here they are, Vladan: the grandpa and grandma of the kids from the film,’ I hear him say, and I know that he is referring to The Sound of Music, the film we saw yesterday. I don’t believe him, because my father likes to make up stories, so I am waiting for a smile to creep on his serious face to reveal that he’s just joking. But this time he ignores my suspicious gaze, and tells me that my birthplace used to be an Austrian town, and that many soldiers are buried in this cemetery who, like him, served their country.

‘This is not a cemetery anymore, it’s one big monument!’ he says, and I don’t understand him, because there are graves everywhere, and not a monument in sight, but he goes on to say that soldiers should still be buried here, as this will continue the rich military history of this town, making this an even bigger and more renowned monument.

I’m still too young for stories about graves and transience and all those tomorrows which will come after us: His words give me the chills, but he just goes on and on, telling me that the names of the dead say everything, and that he, when he first came to Pula, went straight to the cemetery in order to find out where he really was.

‘Our people aren’t here at all. There are Austrians, Germans, Italians, Czechs. That’s history for you, Vladan. Today we are here, tomorrow it’s going be someone else,’ he says, and then we absentmindedly stare towards the grave of August and Hedwiga, George’s parents, and a melody from the film starts buzzing around my head, but I think that I really shouldn’t whistle in a cemetery. Even if it isn’t a cemetery – but a monument.

It’s small, barely visible, this grave of his, hidden well from the curious eyes of uninvited visitors. There is no photograph on the tombstone, no date, and naturally, no name. My father isn’t here, I think for a second, standing over him. Looking around, I’m afraid of someone noticing me, revealing a dead criminal’s hiding place. Tomislav Zdravković lies here, I read again, and hear my drunken father’s voice again, penetrating into my room once more, in the middle of the night, interrupting my attempts at sleep. ‘I hit the bottom of life. And hell and the abyss.’ How many times have I heard this song, and how many times I have I heard my mother whispering from somewhere: ‘Quietly, Nedelko, quietly. Vladan’s sleeping.’

Since Dusha called me and told me that Nedelko died, I’ve been seeing him an awful lot. I see him and her, too, and Emir and Enisa, and everybody’s there. Even though it’s cold outside these days, I can feel summer coming. I can hear Mario whispering during Italian lessons that his father promised him that he could go alone by boat to Fratarski Island, and that I could go with him. Summer is almost here, I can feel that, and every day at lunch, Nedelko keeps repeating the same question: ‘How about we go to the island of Cres or maybe Lošinj this year?’ And my mother and I aren’t sure if he means it, so we don’t reply. ‘We’ve never been on an island,’ he says, while ladling some more soup into his bowl, and I hope that he means it, and that we will really go to the islands, and I can hardly wait for summer, which will begin any day now. June is almost here, and my mother is already ransacking the wardrobe to find my trunks and beach towels.

It’s getting dark, but I’m still standing over Nedeko’s grave, thinking that, after almost seventeen years, I’m still waiting for that unfinished June to continue, and another great summer in Pula to start. And I feel more and more that I’m still the boy who is waiting in room 211 at the Bristol Hotel for him to return home. A boy waiting to return to Pula, where his friends with a boat await him, and his dad will finally take him to the island of Cres or maybe Lošinj, to a large island, even larger than the Brijuni Islands, so large that you can’t even believe that it’s an island. Sinisha went to see his aunt on the island of Krk, and told me that everything was different there than it is here, on the coast.

I’m thinking about my old friends, wondering where they are now and what they’re doing, and I remember how we hit Fat Fred’s ass with a slingshot, and then convinced him that it was a wasp, and then Fred raced home, afraid that he would get an allergic reaction. I feel like laughing again, and then think that Sinisha and Mario, my old friends have been waiting for me in the back garden, behind the shop, for seventeen years, waiting to meet me that day and go to the Valkane swimming area after lunch. It’s only half an hour walk from our apartment building to the sea, and Mario promised that he would take his brother’s deck of cards, while Sinisha promised that he’d bring a rubber ball for the water volleyball game. For seventeen years, they’ve been sitting on those stairs in front of my apartment building, with towels around their necks, waiting for me.

Is everything finally over now, I ask myself? Can I finally go back home and go to the beach with them? Can my summer now finally start, I wonder, as I stare at my father’s grave, as if expecting an answer?

But Tomislav Zdravković doesn’t reply.

Nor does Nedelko Borojević.

THE AUTHOR

Goran Vojnović (b. 1980) graduated from the Academy of Theatre, Radio, Film and Television in Ljubljana, where he specialised in film and television directing and screenwriting. The film Good Luck, Nedim for which he co-wrote the script with Marko Šantić won the Heart of Sarajevo Award and was nominated for the European Film Academy’s Best Short Film Award in 2006. He has directed three short films himself and his first feature film Piran/Pirano premiered in 2010. Vojnović is considered one of the most talented authors of his generation. Film magazines and newspapers regularly publish his articles and columns. His bestselling debut novel, Southern Scum go Home! (2008) reaped all the major literary awards in Slovenia, has been reprinted five times and translated into numerous foreign languages. A collection of his columns from a Slovene daily newspaper and weekly magazine have also been published as a book under the title When Jimmy Choo meets Fidel Castro (2010), which was translated into Serbian. Southern Scum go Home was made into a feature film (directed by the author himself) in 2013, and in spring 2015, Yugoslavia, My Fatherland was staged as a play in the national Drama Theatre, Slovenia.

THE TRANSLATOR

Dr Noah Charney is a professor of Art History at the American University of Rome and the University of Ljubljan

a, Slovenia. He is also an award-winning writer for numerous publications, including The Guardian, The Atlantic, Salon, The Times and Esquire. He is the best-selling author of many books, including The Art Thief (Atria 2007) and The Art of Forgery (Phaidon 2015). He lives in Slovenia, where he collaborates with local authors and publishers on books such as this one.

THE BREAK-UP OF YUGOSLAVIA: IMPORTANT DATES RELEVANT TO THE STORY

30. 6. 1990 – Yugoslavia lost to Argentina in the quarterfinals of the football World Cup. Some would later suggest that only a World Cup win could have kept a country like Yugoslavia together.

25. 6. 1991 – Slovenia declared independence. For some reason many people still believe this is to blame for everything that followed. In Slovenia, on contrary, history starts with this day.

25. 6. 1991 – Croatia declared independence. Whereas in Slovenia, almost everyone was for independence, in Croatia, the large Serbian minority wasn’t at all happy about being separated from Serbia.

26. 6. - 7. 7. 1991 – Ten-Day War in Slovenia. There is a famous TV shot of a young Yugoslav Army soldier trying to explain this war: “They sort of want to separate and we are sort of not allowing them to!”

18. 11. 1991 – Fall of the eastern Croatian town of Vukovar. The Yugoslav Army, or should we say Serbian Army, defeated the Croatian Army and killed the city and many of its residents along the way. By this point, this Balkan War had everything a proper war usually has; concentration camps included.

5. 4. 1992. – The last march for peace in Sarajevo ended with Serbian snipers killing Suada Diberović and Olga Sučić. Soon after, Sarajevo would come under a military siege that would last for three years.

11. 7. 1995. – The fall of the Bosnian town of Srebrenica: The Serbian Army, under the command of General Ratko Mladić, entered the UN protected zone of Srebrenica and in the next four days killed more than 8,000 people.

14. 12. 1995 – Slobodan Milošević, Franjo Tuđman and Alija Izetbegović signed a peace deal in Paris, previously negotiated in Dayton, but they all died before they could get the Nobel Peace Prize for it.

24. 3. 1999 – Beginning of the NATO bombing of Serbia: the first NATO action in Europe was also the last chapter of the Balkan Wars.

28. 6. 2001 – Slobodan Milošević is deported to the International Criminal Tribunal in The Hague. The Serbian president died in prison of a stroke before being sentenced by the court.

17. 2. 2008 – Kosovo declared Independence. This is the last part of Yugoslavia to declare independence, but Kosovo is still to become an internationally recognized country.

21. 7. 2008 – Radovan Karadžićis arrested. Before becoming a war criminal, Radovan Karadžić was a psychiatrist and poet, writing poetry for children.

26. 5. 2011 – Ratko Mladić is arrested. Before deportation, Serbian authorities allowed Ratko Mladić to visit his daughter’s grave. She had committed suicide.

Table of Contents

YUGOSLAVIA, MY FATHERLAND MAP OF SFR YUGOSLAVIA

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

THE AUTHOR

THE TRANSLATOR

THE BREAK-UP OF YUGOSLAVIA: IMPORTANT DATES RELEVANT TO THE STORY

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland

Yugoslavia, My Fatherland